“You may not believe me; I have news about the drought: Good news, better news, best news and a bonus.”

There is an overall increase of 13.3% income per cow and over 90% of the milk cows in the Dry Zone ranges between 4 to 8 liters per day. Do you know that the income by selling milk compensated the farmer’s losses incurred from crop failures during this period? That’s the good news as the farmer with dairy cows received 46.1% more income during this Maha season. The drought had an encouraging effect on milk production by increasing it by 77% during this period. That’s the better news. The cost of production of a liter of milk in the Dry Zone is between Rs 10 to 25 and the sale price is between Rs 65 to 85. Hence, the turnover is between 300 to 700%. Now that is the best news.

“Can any agriculture enterprise match this?”

Furthermore, consuming milk from the Dry Zone cattle is ecologically sensible as these cows are a part of an integrated agricultural system that raises crops primarily for human food. No dedicated crops were grown for them. Their diets are mainly human food crop residue and naturally growing grasses.

The prevailing drought condition severely affected paddy and highland crop cultivation. Land preparation and planting paddy and highland crops can stretch from the beginning of September, October to November. It is safe to say that this expenditure could be around Rs 40,000 per acre in both paddy and highland cropping and will be recovered after the sale of the harvest at the end of season. But it was not to be, this time, as the prevailing drought destroyed their crops.

However, farmers with dairy cattle recovered this amount within 3 months (Table 1).

Table 1: Cash flow Statement of Crop-Livestock Farmer–Holding with One acre and One milking cow

| One acre / One cow | Average milk production | Average milk sale price | Income Rs. | Costs Rs. | Loss | Profit |

| Sept -Oct | 4.000 lts/day/cow | Rs 67.0 / liter | 20,435.00 | 42,440 | (22,005) | |

| November | 5.753 lts/day/cow | Rs 67.5 / liter | 11,649.83 | 2,558 | (12,913) | |

| December | 6.088 lts/day/cow | Rs 68.0 / liter | 12,833.50 | 3,397 | (3,477) | |

| January | 6.841 lts/day/cow | Rs 69.0 / liter | 14,632.90 | 4,242 | 6,915 | |

| February | 7.861 lts/day/cow | Rs 70.0 / liter | 15,407.56 | 4,622 | 17,700 |

With the advent of the Maha season farmers being busy with land preparation followed by crop cultivation will have less time for attending to livestock activities. In this period cattle and other ruminants are restricted to prevent any crop damage and easy management. The consequence of this restriction results in a low feed intake and a very little milk is procured during Maha as compared to the Yala season. However, due to the drought conditions in 2016/17 Maha season this has changed. This season paddy land and highland is mostly abandoned, but it has a luscious growth of grass, remnants of the failed crop and few wet patches due to intermittent rain. One other thing is grazing herds are visible in these abandoned crop fields and tank beds. (Image 2) This situation has allowed the milking herd to consume sufficient herbage to provide nutrients required for body maintenance and production. However, unlike in a normal year these animals were able to maintain a good body condition and a nutrient reserve throughout the year that may have indirect results such as increasing milk production, prolonged lactation period, increasing fat percentage and increase in the number of calving’s that will initiate milk production. The added income through these direct and indirect benefits will support total farm activities in this crop-livestock mixed farming system. The following image shows cattle grazing in tank bed during Maha 2016/2017, they look well fed.

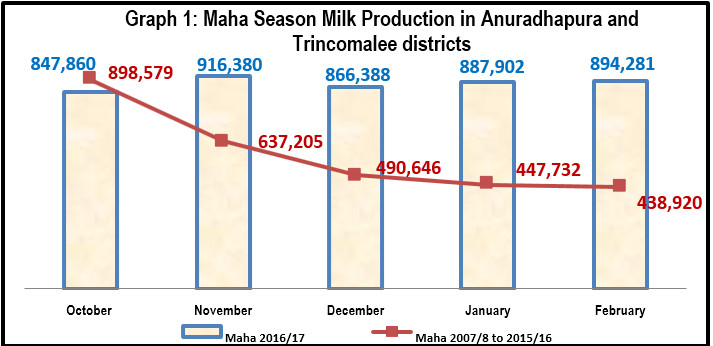

The graph 1 shows gain in milk production by 43.8%, 76.6%, 98.3% and 103.7% in the months of November, December, January and February respectively. This is opposite to what we usually witness in a regular Maha season (from 2007/08 to 2015/16) with normal rainfall.

Poor nutrition in the Maha season can cause severe problems in the cattle population. Indigenous cattle breeds are less affected but crossbreds with European and Indian blood showed poor growth, shorter lactation period and longer calving intervals. Poor body condition score is apparent with visible hips and pin bones, outline of 3 to 5 ribs and outline of spine. Some of these features can be observed in image 1.

Yet, after the Maha harvest ample amount of feeding will allow these cattle to recover and increase milk production. However, during the 2016/17 Maha season there is sufficient amount of feed to maintain a favorable body score. That will reflect in increased lactation period by about 30 days and reduced calving interval by about two months.

Ruminant Milk and Meat production is predominantly a grazing farming system. This grazing farming system has failed to produce milk consistently throughout the year and supply milk to meet the demand. This is due to the quality of herbage available for grazing and also owing to the lack of feed at critical times. In the past they were allowed to graze in forest and marginal pasture lands, in addition to uncultivated land in the Yala season (dry period) where irrigated water is provided only to cultivate around 30 – 40% land.

Table 2: Land Use for Grazing – Past

| Grazing Area | Yala (Irrigated) | Maha (Rain fed) |

| Forest | Grazing | Grazing |

| Pasture & Scrub land | Grazing | Grazing |

| Paddy Lands | Grazing 40% | No grazing 100% cultivated |

| Highland | Grazing 45% | No grazing 100% cultivated |

Later, government regulations prevented ruminant grazing in forest and marginal pasture land (Table 3).

Table 3: Land Use for Grazing in Dry Zone – Current

| Grazing Area | Yala Season (Irrigated) | Maha Season (Rain fed ) |

| Forest | No Grazing | No Grazing |

| Pasture & Scrub land | No Grazing | No Grazing |

| Paddy Lands | Grazing 37.8% | No grazing –1,505,796ac cultivated |

| Highland | Grazing 45% | No grazing 100% cultivated |

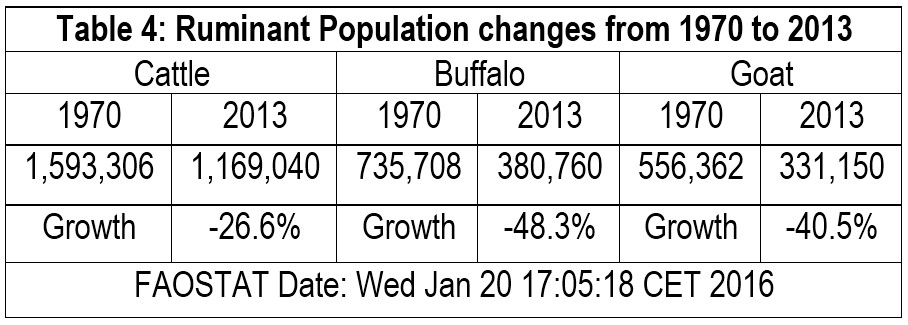

The effect of this is the drastic reduction of ruminant population during the past several decades (Table 4) as farmers were unable to maintain livestock, especially ruminants. In addition, the new paddy harvesting practice through heavy machinery prevents the use of rice straw.

However, there will be a fresh problem to the Dry Zone farming system with the new irrigation projects being able to provide sufficient irrigated water to cultivate rest of the land during the Yala season (dry period) for only human food (Table 5).

Table 5: Land Use for Grazing in Dry Zone – Immediate future

| Grazing Area | Yala Season (Irrigated cultivation) | Maha Season (Rain fed) |

| Forest | No Grazing | No Grazing |

| Pasture & Scrub land | No Grazing | No Grazing |

| Paddy Lands | No Grazing – 100% Cultivated | No Grazing – 100% Cultivated |

| Highland | No Grazing – 100% Cultivated | No Grazing – 100% Cultivated |

This will have a major consequence on the growth of the ruminant population, as this farming system will be completely cut off from land. Hence, it is essential to transform this traditional grazing milk production system to a stall feeding system in the Dry Zone. However, this is not possible unless an intervention to the feeding and breeding system is introduced.

Key lessons learnt:

- Modes of interventions not focused to the real problem for a paradigm shift.

- Annual Loss of 2.2 million liters in Anuradhapura and Trincomalee area.

- Continuation of the Practice of grazing (free grazing) system in Dry Zone.

- Demand for replacement stock higher than the current supply as current Artificial Insemination is inadequate to increase supply.

- Seasonality of availability of feed – No measures to increase shelf life of crop-residue and grass.

- Starvation and water deprivation effect on body physiology of cattle – Restriction to prevent crop damage during rainy season.

- Difficulties of women headed families to rear cattle – Unable to take animals for grazing to distance places.

Impact needs to be generated:

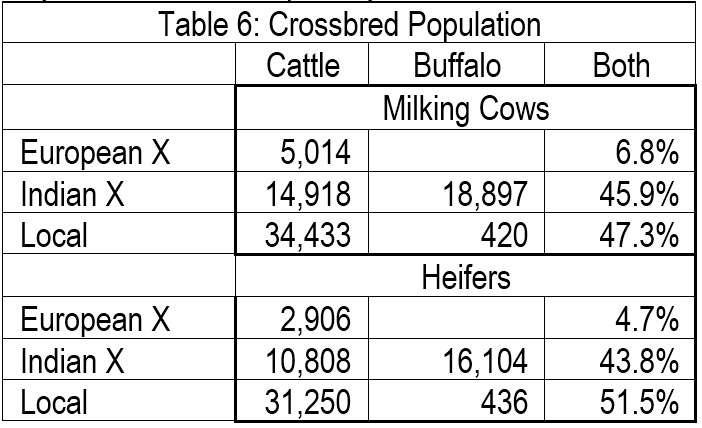

- Increasing cross bred population through artificial insemination (AI) and organized natural breeding system. Currently crossbred pregnant heifer cost Rs 120,000. Half the population is of the indigenous types yielding 2 – 3 liters per day. Hence, to do any intervention that will result in a paradigm shift there is a need to increase the crossbred population that will yield 10 to 15 liters per day.

- The Department of Animal Production and Health during the past 50 years made a concerted effort to increase the number of crossbred cattle in Sri Lanka despite various constraints.

- The AI programs have the capacity to supply around 40% of the required replacement and the rest either takes a long time to conceive or bred by using a non-descript male not suited to supply daughters that can produce more milk. It is the milk marketing organizations that will benefit from every calving, as it results in the inception of milk production.

- Hence, it will be advantageous to have a national program for Natural Breeding. This activity has to be a combined effort between DAPH, NLDB and Milco (government owned milk marketing organization) through using good quality Jersey males from the National Livestock Development Board (NLDB). This program should locate one such stud-unit per milk collecting centre.

- A member of this milk collecting centre will be responsible for maintaining this stud-centre where he is economically benefited and compensated for the use of the stud bull for natural breeding by other members.

- Promotes the development of food-feed system as land is a limiting factor for human food production. New intervention to utilize the next major crop – maize – as a livestock feed which was explored and was successful. In this crop, after selling the cobs as human food the residue will be converted to silage and utilized for feeding ruminants with better results than other crop-residue.

- One acre of maize yields 10-15 metric tons stalk that can be converted to a nutritious feed called silage that can be fed to an adult cow for a period of two years. The stalks has to be chopped, crushed and packed in anaerobic condition. This can be fed after three weeks of storage. This not only increases the shelf-life of these crop-residues but also improve their nutritive quality.

- Promote utilization of machinery – Choppers (Rs 75,000), milking machine (Rs 95,000) and sprinkle irrigation system for maize (Rs 60,000 to 100,000 per acre). A soft loan of Rs 200,000 and a grant of Rs 60,000 to purchase this equipment under the supervision of the Department of Animal Production is a good investment.

It is not a surprise that the local milk supply is still below 30% of the demand after years of various other interventions that took place. However, with the change in strategy i.e., transforming free-grazing practice to stall-feeding, the Sri Lankan farmers could be able to double the milk production in three years – 2020. Now this is a bonus.