An article by - Prof. Meththika Vithanage (Ph.D. in Hydrogeology; Prof. in Natural Resources) Director, Ecosphere Resilience Research Centre, Faculty of Applied Sciences, University of Sri layewardenepura [email protected]

With more than two third of the world is under lock down due to Covid-19, many countries are facing problems that they have never encountered before. Those problems range from quarantine issues to last rights of the people die from this infection.

In a viral pandemic like COVID-19, the concern is that the dead bodies of victims can spread the virus among the people who closely handle or work with them. At the same time there is a huge debate on whether burying the bodies of COVID-19 victims may facilitate the viral spread through the ground water table.

In this article we try to look back at scientific literature and review the risk of ground water contamination through the burial of viral disease victims’ dead bodies.

It has been a well-known fact that the cemeteries are among the chief anthropogenic sources of pollution and contamination of groundwater in urban areas and beyond, in the area of hydrogeology. In the process of decomposition of a human body, 0.4-0.6 liters of leachate is produced per 1 kg of body weight, which may contain pathogenic bacteria and viruses that may contaminate the groundwater. Burial in any means causes soil contamination and then leads to groundwater pollution via the discharge of inorganic nutrients, nitrate, phosphate, ammonia, chlorides etc. and various microorganisms. High biochemical and chemical oxygen demands, ammonia, and organic carbon have been reported as high as several hundreds of mg in L from cemeteries and mass burial sites.

In the case of viruses, recent studies indicate that viral may transport in soil with rainfall infiltration and extends specifically to drinking water from an untreated groundwater source. Several scientific publications report virus occurrence rates of about 30 percent of groundwater. Virus transport in groundwater is associated with a high degree of temporal and spatial variability, which is often attributed to absorption, filtration, soil water content, temperature, pH, type of virus, and hydraulic stresses and climatic conditions. It has been observed that viruses in groundwater can be correlated with their concentrations in wastewater and with groundwater recharge events. The ex-filtration from sewers and cemeteries are the most likely source of human viruses to this groundwater system, and leakage from sewers during heavy precipitation enhanced virus transport. The transport is often associated with both the unsaturated and saturated subsurface composed of varying geological settings with corresponding hydro-geological variability. Included among the essential hydro-geological factors that can be used to evaluate viral transport are the flux of moisture in the unsaturated zone, the media through which the particles travel, porosity, the length of the flow path, and the time of travel. In Sri Lanka, we experience high rainfall, low groundwater table, highly porous subsurface soil, and fractured rocks compared to most temperate countries in the world, which may lead the transport of biological and chemical compounds from dead bodies. Although WHO recommendation guidelines suit temperate countries mainly, not tropical high-temperature high rainfall countries where we experience high decomposition rates and highly variable water table. This is where the local hydro-geological knowledge is essential to protect groundwater as well as forthcoming infection occurrence. Given the vulnerability of our groundwater aquifers, and lack of understanding about the behavior of COVID-19 virus, there can be a risk from dead bodies, septic waste or sanitary waste are having any contact with water sources. Hence, it is advisable to have careful measures in destroying the infected dead bodies, septic, and sanitary waste in proper conditions without provisioning chances for any future disease outbreak.

References

- Azadpour-Keeley, A. and Ward, CH. (2005), Transport and survivat of viruses in the subsurface — processes, experiments, and mulation models. Remedition, 15: 23-49. doi:10.1002/rem.20048

- Gothowrtz, M. B., et al. (2016). “Effects of Climate and Sewer Condivon on Virus Transport to Groundwater.” Environmental Soence & Technology $0(16):

- Morgan O. Infectious disease risks from dead bodies following natural disasters. Rev Panam SaludPublica, 2004; 15(5):307-12.

- Jozef Zychowski, Tornasz Bryndal; Impact of cemeteries on groundwater contamination by bacteria and viruses — a review. J Water Health 1 June 2015; 13 (2); 285-301. doi: 10.2166/wh.2014.119

- Ueisik, A. S. and W.H.O.R.O. f. Europe (1998). The impact of cemeteries on the environment and public health: an introductory briefing, WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Oliveira, B., Quintero, P., Caetano, C_, Nadais, H., Arroja, L., Ferreira da Silva, E. and Senos Matas, M. (2023), Burial grounds impact. Water Environ J, 27:99-106. doi:10.1111/j.1747-6593.2012.00330.x

- Abia, AL. K., et al. (2019). “Microbial life beyond the grave: 16s rRNA gene-based metagenomic analysis of bacteria diversity and thew functional profiles in cemetery environments.” Science of The Total Environment 655: 831-841.

Featured Image – Sandun Arosha F’do ( @sandunarosha )

WHO guide lines do not specify that it is compulsory to cremate dead bodies of covid 19 victims. They have laid out guidelines for cremation as well as burial.

Debunking the Claim Against Burial of COVID-19 Victims: A layman’s response to Professor Vithanage

By Althaf Marsoof

The decision of the Sri Lankan Government to cremate bodies of COVI-19 victims has been (and still is) a controversial one, giving rise to both legal and scientific concerns. I have dealt with the legal concerns, particularly regarding the extent to which the Government’s decision impacts fundamental rights guaranteed under the Constitution of Sri Lanka, in a publication elsewhere (Marsoof 2020). But here, I deal with the views expressed by Prof. Meththika Vithanage, who strongly believes that bodies of COVID-19 victims ought not to be buried. In an article published in April 2020, she claims:

“Although WHO recommendation guidelines suit temperate countries mainly, not tropical high-temperature high rainfall countries where we experience high decomposition rates and highly variable water table. This is where the local hydro-geological knowledge is essential to protect groundwater as well as forthcoming infection occurrence. Given the vulnerability of our groundwater aquifers, and lack of understanding about the behavior of COVID-19 virus, there can be a risk from dead bodies, septic waste or sanitary waste are having any contact with water sources.”

Her views appear in an online publication available at the following link:

http://scientist.lk/2020/04/07/science-behind-burying-the-covid-19-infected-dead-bodies/#comments

I am no scientist, but out of curiosity, I took a look at the sources she had cited to reach her conclusion. Based on a reading of those sources, I make the following observations from a purely layman’s point of view.

1. Prof. Vithanage begins by stating “Burial in any means causes soil contamination and then leads to groundwater pollution via the discharge of inorganic nutrients, nitrate, phosphate, ammonia, chlorides etc. and various microorganisms.” From what I understand, however, viruses such as COVID-19 are not regarded as microorganisms. This distinction is an important one, as viruses cannot survive for long without a host, and evidence suggests that “coronaviruses are more rapidly inactivated in water and wastewater at ambient temperatures” (Gundy et al 2009). Therefore, Prof. Vithanage’s statement reproduced above is seemingly contradictory to her main thesis.

2. The issue of microbial/viral contamination of groundwater isn’t a new issue. Interestingly, the first source Prof. Vithanage cites concludes that “[t]here are indications that the inactivation rate of viruses is the single most important factor governing virus transport and fate in the subsurface.” (Azadpour-Keeley and Ward 2005, 41).

However, when the above finding is considered in light of a more recent peer-reviewed publication, it appears that the risk of COVID-19 contaminating groundwater and remaining infectious is extremely low, if not nil in light of the climatic conditions in Sri Lanka:

“The data available suggest that: i) CoV seems to have a low stability in the environment and is very sensitive to oxidants, like chlorine; ii) CoV appears to be inactivated significantly faster in water than non-enveloped human enteric viruses with known waterborne transmission; iii) temperature is an important factor influencing viral survival (the titer of infectious virus declines more rapidly at 23°C–25 °C than at 4 °C); iv) there is no current evidence that human coronaviruses are present in surface or ground waters or are transmitted through contaminated drinking-water” (La Rosa et al 2020).

3. Prof. Vithanage cites a peer-reviewed article dealing with “Effects of Climate and Sewer Condition on Virus Transport to Groundwater” (Gotkowitz et al 2016). It appears that by doing so, Prof. Vithanage is trying to draw a parallel between sewer systems and burial grounds – to claim that conditions at burial grounds could result in contamination of groundwater. While this analogy may be reasonable, what must be noted is that the same study makes the following finding:

“Unexpectedly, a severe regional drought occurred during the initial months of this project, resulting in reduced infiltration through the vadose zone, an increase in soil temperature, and low water table elevation. We suggest that these conditions inhibited virus transport from sewers to the water table, resulting in a low virus detection rate, 3.7%, compared to a 2008 study at some of the same sites and wells” (Gotkowitz et al 2016, 8502).

This finding is significant, as it opens up the possibility of using land in the dry zone of Sri Lanka, where the soil temperature is higher and the water table is lower, for the purposes of burying victims of COVID-19.

4. Next Prof. Vithanage cites a peer-reviewed paper on the “Impact of cemeteries on groundwater contamination by bacteria and viruses” (Zychowski and Bryndal 2015). However, this paper does not claim that bodies of victims infected with a virus should not be buried. It merely makes a number of recommendations pertaining to the location and nature of cemeteries and precautions that those who handle dead bodies should take. As such, this reference does not support her claim that bodies of COVID-19 victims should not be buried.

5. Next, Prof. Vithanage cites a report of the WHO’s regional office for Europe, which deals with the impact of cemeteries on the environment and public health. However, the said publication merely provides recommendations pertaining to factors that must be taken into account in determining places to be used as cemeteries – and in no particular sense suggests that bodies of those who died of viral infections should not be buried. In fact, the report goes on to state that “viruses are fixed to soil particles more easily than bacteria and they are not carried into groundwaters in large numbers” (WHO 1998, 8), which significantly dilutes Prof. Vithanage’s claim about viral contamination of groundwater.

6. Prof. Vithanage cites two further sources that seek to link cemeteries as a source of groundwater contamination. The first study is by Oliveira et al (2012), where the authors observe that “the most critical parameters when assessing the pollution potential of a burial ground are inhumation depth, geological formation, depth of the water table, density of inhumations, soil type and climate.” Again, this paper makes recommendations of factors that authorities must consider before selecting areas to be designated as cemeteries. Nothing in this paper suggests that bodies of those who die of viral infections such as COVID-19 ought not to be buried.

The second study by Abia et al (2019) focuses solely on cemeteries as a source bacterial contamination of groundwater. Therefore, this study does not help Prof. Vithanage’s claim as regards the COVID-19 virus.

7. As a final point, and quite strangely, Prof. Vithanage cites a study by Morgan (2004) titled “Infectious disease risks from dead bodies following natural disasters”. However, in this study the author observes:

“Disposal of bodies should respect local custom and practice where possible. When there are large numbers of victims, burial is likely to be the most appropriate method of disposal. There is little evidence of microbiological contamination of groundwater from burial”

Clearly, it is unclear how Morgan’s study in any way supports Prof. Vithanage’s claim that bodies of victims who die of COVID-19 should not be buried. In fact, it supports the exact opposite – that scientifically there is no objection in burying bodies despite such bodies being a potential source of infectious disease.

The seven points set out above demonstrate that there are some grave errors and contradictions in Prof. Vithanage’s claim that bodies of COVID-19 victims ought not to be buried in view of the potential risk of groundwater contamination. If Prof. Vithanage’s claim is based on the sources she has cited in her April publication, then, her claim is extremely difficult to justify.

Of course, I make these remarks as a layman to the field of science and, therefore, I am open and willing to be corrected. But on the face of it, it seems to me that Prof. Vithanage’s claim attracts no support from the very authorities she uses to support her claim. And indeed, if her claim is true, the focus must not merely be limited to the disposal of bodies of COVID-19 victims but should extend to the management of waste from hospitals where COVID-19 patients are treated and sewage from residences where COVID-19 patients are quarantined and reside. After all, these are all possible sources from which groundwater may be contaminated!

References

Abia AKL et al 2019. Microbial life beyond the grave: 16S rRNA gene-based metagenomic analysis of bacteria diversity and their functional profiles in cemetery environments. Science of the Total Environment, vol 655: 831–841.

Azadpour‐Keeley A and CH Ward 2005. Transport and survival of viruses in the subsurface—processes, experiments, and simulation models. Remediation-the Journal of Environmental Cleanup Costs Technologies & Techniques, vol 15: 23-49.

Gotkowitz MB et al 2016. Effects of Climate and Sewer Condition on Virus Transport to Groundwater. Environmental Science & Technology, vol 50: 8497-8504.

Gundy et al 2009. Survival of Coronaviruses in Water and Wastewater. Food and Environmental Virology, vol 1: 10-14.

La Rosa G et al 2020. Coronavirus in water environments: Occurrence, persistence and concentration methods – A scoping review. Water Research, vol 179: 1-11.

Marsoof A 2020. The Constitutionality of Forced Cremations of COVID-19 Victims in Sri Lanka. People’s Rights Group of Sri Lanka, 8 November 2020 [online].

Morgan O 2004. Infectious disease risks from dead bodies following natural disasters. Rev Panam Salud Publica, vol 15: 307-312.

Oliveira B et al 2013. Burial grounds’ impact on groundwater and public health: an overview. Water and Environmental Journal, vol: 27, 99-106.

Vithanage M 2020. Science behind burying the COVID-19 infected dead bodies. The Sri Lankan Scientist, 7 April 2020 [online].

Zychowski J and T Bryndal 2015. Impact of cemeteries on groundwater contamination by bacteria and viruses – a review. Journal of Water and Health, 13: 285-301.

Sir, this is timely appropriate as well as very important feedback. This will surely an eye open to many scholars and knowledge seekers.

The Muslim community in Sri Lanka is dismayed by the enforced cremation of dead bodies by the authorities. It has now become a tug a war among the professionals. This article aims at shedding light into scientific background of the issue. The reason for the denial of burial rights is ground water contamination as explained by the health authorities.

However various local and international experts claim that the coronavirus does not accumulate within dead bodies and the virus is not found to be water borne. The term groundwater contamination was specified in the guidelines published by the ministry of health and repealed suddenly. It was stipulated to cover in the body bag and coffin, and buried at six feet depth (deep burial) then it was specified as (exact sentence is quoted) “it should not contaminate with the groundwater”.

Here confusion arises to which phenomenon the phrase refers to. It was later perceived to include the environmental concern of the burial from the academic discourses of various people who advocate for cremation. Therefore the tricky piece of the “groundwater contamination” due to burial of dead bodies is such that it has two aspects, namely change of environmental conditions and viral spread via water and both are weighed out of proportionally.

When religious clergy or ignorant politician tend to emphasize for respecting religious values and merely quoting WHO provisions in hope for a solution without establishing sound argument in light of scientific facts; the issue takes political turn. There is a popular outcry from the majority Sinhala Buddhists for following science than religion and equal treatment irrespective of creed or race. It is very crucial to note that in Islamic jurisprudence something that is unhealthy or unsafe is not obligatory to be undertaken.

1. Decay of body and pollution from organic compounds

Burial of dead bodies is an ancient practice by mankind for centuries. When dead bodies are buried certain change of conditions of environment occurs due to biodegradation of organic matter and seepage of leachate from the bodies to ground water or surface water.

However little attention is paid by the community and the government even for very higher level of pollution from garbage and sewage. If we quantify the BOD. COD. total Nitrogen Phosphorus, and heavy metals ect. (in comparison) one may conclude that the pollution due to dead bodies is very insignificant

Prevailing situation of the country enables people to come up with undergraduate course work type articles and bluster about the pollution providing quantities of leachate ect. However no test results around the burial grounds were provided to support their argument.

Even if there is a significant harm is envisaged that can be mitigated by the application of science (so-called). For example Insulation, leachate collection and treatment are widely practiced engineering applications. It is unfortunate to note that some perceived as experts portray as if there is no mitigation to be done. Hence it is very disturbing to accept this discrimination by the well-informed Sri Lankan Muslim community.

On the other hand cremation may seem to be a better solution for making sure no virus is left however it can cause irreparable air pollution. Scientific evidence proves that crematoriums emit harmful pollutants which are associated with serious health problems for which children are vulnerable. These pollutants include mercury, dioxins, dibenzofurans, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide and hydrogen chloride

2. Spread of Virus in the groundwater

Upon death of the patient, virus stop replication of its RNA from the host cells and they begin to die. It remains inactive in side the body and on the surface for a little time. When the body is prepared for disposal most of the virus vanish from the applied sterilization agents. Though for the sake of ensuring maximum safety, it is assumed that some virus remain in the dead body. When the body is buried there is a very little possibility for the pathogen to come out of the body bag and coffin. However it is once again assumed that some virus to enter into groundwater..

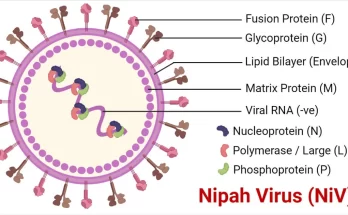

The virus SARS-COV-2 that causes COVID-19 disease is an enveloped one, with a fragile outer membrane. Generally, enveloped viruses are less stable in the geo- environment and eventually die off. So it can be concluded that it is impossible for disease Covid 19 to spread via the the ground water due to burial. However there has been very high attention and publicity in the media due to the panic situation in the country. It is not a secret now that certain media spew racial hatred. It was an exaggeration

Further to that the following instances where virus release into the ground water is provided to support the inability for viruses to transmit via groundwater Virus may be released into the water ways and ground water from the people who are contagious while they are in quarantine or unidentified condition This has been never accounted because Covid19 is not yet found to be a water spread. Water from bodies of living animal and leachate from the dead animals is directly discharged to the ground. Viral spread from this too seldom concerned.

Conclusion

Burial of dead bodies causes certain insignificant yet repairable change of environmental condition with impossible water spread of covid-19. Whereas cremation causes significant and irreparable air pollution at the expense of religious harmony.

Acronyms

BOD – Biochemical oxidization Demand

COD – Chemical oxidization Demand

RNA – Ribonucleic acid

*Eng. A. J. A. H. Jowsi, Charted Environmental Engineer

So we are to believe what muslim clerics and religious books say, and what non-scientists like you say? Better to understand that islam is just another religion. Scientific methodology and approach is broader than religion and is based on fact, not faith. No amount of Belief make something a Fact. unless muslim community do not get this, the problem will persist. Governments and medical authorities are not here to appease muslims and islam.

If all other religions in SL understand this, and muslims don’t understand it, the problem is in your religion islam, and it’s addherents, it’s strictness, inflexibility and dogma. No point in blaming anyone.

Would like to know what are the authorities going to do regards to covid patients who use the toilets? Weather it be a drainage line, septic tank or even a normal rural area toilet that a patient uses? This certainly could be worse than a dead person being buried.

COVID-19 Myths Vs Science

Can COVID -19 be transmitted through water? Or Mosquitoes? Is COVID-19 transmission affected by weather? Dr Sylvie Briand busts popular myths about COVID-19 in this edition of Science in 5, WHO’s conversations in science.

https://youtu.be/Iy1xeIVeRwY

Groundwater, Wells, and Coronavirus

By William M. Alley, Ph.D., and Charles A. Job

The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 (officially known as SARS-CoV-2 but referred to here as the COVID-19 virus) has not been detected in drinking water in either private wells or public drinking water systems.

Human feces would be the most likely source of the COVID-19 virus in drinking water, but according to the World Health Organization, “the risk of catching COVID-19 from the feces of an infected person appears to be low.”¹

Filtration and disinfection methods used in most municipal drinking water systems should remove or inactivate viruses. Despite the low risks, the question has arisen about the vulnerability to COVID-19 of homeowners with private wells and those who rely on untreated public groundwater supplies.

We address this question for private well owners by reviewing (1) viruses in groundwater in general and specific characteristics of the COVID-19 virus as it relates to groundwater, (2) septic systems as a potential source of COVID-19 virus to private wells, and (3) treatment systems for private wells.

Viruses in Groundwater

In general, groundwater contains fewer microbial contaminants (pathogens) than surface water, yet the biological integrity of groundwater cannot be taken for granted.² Approximately half of all waterborne disease outbreaks are associated with contaminated groundwater.³

Many of these outbreaks are from wells that serve businesses or small water systems that do not require water disinfection and have minimal microbial monitoring requirements. People drinking from household wells also can become exposed to waterborne pathogens, but these outbreaks are less well documented.

Pathogens can be introduced to groundwater through septic tanks, leaking sewers, and land applications of livestock manure and septage, among other sources. Groundwater contamination also can occur from poor well design and construction.

A proper sanitary seal around the well casing is essential to block contaminants that might migrate from the land surface down the outside of the casing (well annulus) to the water table, bypassing the unsaturated zone that naturally helps cleanse groundwater.

Human enteric viruses (those that replicate in the intestinal tract of humans) are among the microbial contaminants of greatest concern in well water. Common enteric viruses are shed in human stool in enormous numbers and commonly tied to disease outbreaks.4

Reduction of pathogens in the subsurface generally relies on three processes: filtration, adsorption, and die-off/inactivation.

Filtration results when the pathogens are too large to fit through the soil or aquifer pores and cracks. The extent of filtration depends on the type of soil and rocks through which groundwater flows. For example, silts are more effective at trapping microorganisms than sands.

Filtration reduction also depends on the size of the organisms. Physical removal by pores is less effective for viruses than other pathogens because of the very small size of viruses.

Adsorption occurs when the microorganisms become attached to particles, which removes them from the water or at least delays their transport. Virus adsorption onto sediment grains is considered the primary removal mechanism in soils and groundwater, with a complex dependence on the chemistry of the sediment and water.

Travel time can be important because viruses lose their infectivity with time in the subsurface, dependent on temperature, pH, and other factors.

Soils have been found to be effective at virus removal. Rates of removal and restriction are dependent on soil texture, composition, and reactions occurring within the soil layer. At the same time, wells in certain types of aquifers, such as karst and fractured rock, are susceptible to enhanced virus transport.5

The COVID-19 Virus

The COVID-19 virus is a respiratory virus that spreads by droplets from coughs and sneezes and by contact with contaminated surfaces. Coronaviruses are enveloped, single-stranded RNA viruses that range from 0.060 to 0.220 microns in size. Enveloped viruses are less stable in the environment than nonenveloped viruses.6

The COVID-19 virus has been detected in the feces of some patients diagnosed with the coronavirus. The amount of virus released from the body (shed) in stool and whether the virus in stool is infectious are not known.

The risk of transmission of COVID-19 from the feces of an infected person is expected to be low, based on data from previous outbreaks of related coronaviruses such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome). There have been no reports of fecal-oral transmission of COVID-19 to date.7

Previous coronaviruses have been reported to die off rapidly in wastewater, with a 99.9% reduction in two to three days. Coronaviruses might survive for weeks in groundwater based on limited studies of water.8

Septic Systems and Setbacks

The main potential sources of viruses for homeowner wells are onsite decentralized wastewater treatment (septic) systems and sewer lines. Properly operated septic systems are designed to protect wells from contamination by pathogens, although outbreaks associated with septic systems continue to be reported. Particular concerns are associated with areas having high septic system densities.9

A key concept recognized in local building codes across the nation is “setback”—a requirement that a water supply well be at least a certain distance from a septic system or sewer line to ensure adequate time for sufficient natural degradation of chemicals and die-off of harmful organisms that may endanger well water.

The setback approach as a barrier to contamination of wells is similar to the concept of wellhead protection—to keep potential sources of contamination away from wells. Setback distances take into account the soils and subsurface geology of an area or state to enable chemical degradation and pathogen die-off/inactivation to occur.

As examples, setback distances for homeowner wells from septic leach fields in Minnesota are 50 feet except for special cases.10 The minimum setback of a septic field from a water well in Colorado is 50 feet, but through variance the minimum setback may be 25 feet based on the hydrogeologic information for the site.11

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) expects a properly managed septic system to treat the COVID-19 virus the same way the system manages other viruses often found in wastewater.12

A second line of defense is well and septic system maintenance. Stormwater can pick up and carry viruses and other pathogens. During times or seasons of flooding, cracks in the well casing, riser, and apron around the wellhead can allow floodwater to enter the well and the annular space around the casing below ground.

Wells may be more vulnerable to contamination from viruses after flooding, particularly if the wells are shallow, have been dug or bored, or have been submerged by floodwater for long periods of time.13 Well disinfection may be required to eliminate the virus, which should be followed by a water test.

Treatment

In addition to the use of setbacks for wellhead protection and maintenance of wells and septic systems, water treatment is an optional third line of defense. Distillation, ultraviolet (UV) treatment, and reverse osmosis technologies are effective at virus removal at a household level as point-of-entry/point-of-use equipment.14

After flooding, household water from wells can also be boiled as a means of disinfection for viruses. Boiling water kills or inactivates viruses and other pathogens by using heat to damage structural components and disrupt essential life processes of the microbes.15

To maximize protection, if a well has been flooded, the well water should be tested by qualified (certified/licensed) laboratories and, if testing positive for fecal indicator organisms, should be disinfected by a qualified water services contractor.16

Conclusions

Drinking water from private wells presents a low risk for COVID-19, especially compared to direct human-to-human transmission or by touching a contaminated surface. By far and away, the best protection against COVID-19 is to follow the public health recommendations for social distancing, washing hands, and other measures.

Concerns about the COVID-19 virus in groundwater serve as a reminder of the importance of protecting against pathogens through proper care and maintenance of wells and septic systems.

The EPA, the National Ground Water Association, and many states recommend annual testing of private wells that includes indicator bacteria, analogous to an annual health checkup with a doctor.17 Inspection and maintenance may also be needed if problems are suspected.

Some home treatment systems, but not all, are effective against viruses when properly maintained. By itself, COVID-19 is not a reason to start drinking bottled water or installing home water treatment systems.

References

[1] World Health Organization. Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19). March 9, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses

[2] Alley, W.M., and R. Alley. 2017. Pathogens. In High and Dry: Meeting the Challenges of the World’s Growing Dependence on Groundwater, 195-202. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[3] Craun, G.F., et al. 2010. Causes of outbreaks associated with drinking water in the United States from 1971 to 2006. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 23, no. 3: 507-528.

[4] Borchardt, M.A., et al. 2003. Incidence of enteric viruses in groundwater from household wells in Wisconsin. Applied Environmental Microbiology 69, no. 2: 1172-1180; Wallender, E.K., E.C. Ailes, J.S. Yoder, V.A. Roberts, and J.M. Brunkard. 2014. Contributing factors to disease outbreaks associated with untreated groundwater. Groundwater 52, no. 6: 886−897; Borchardt, M.A., S.K. Spencer, B.A. Kieke, E. Lambertini, and F.J. Loge. 2012. Viruses in non-disinfected drinking water from municipal wells and community incidence of acute gastrointestinal illness. Environmental Health Perspectives 120, no 9: 1272−1279.

[5] Borchardt, M.A., et al. 2011. Norovirus outbreak caused by a new septic system in a dolomite aquifer. Groundwater 49, no. 1: 85-97.

[6] Gundy, P.M., C.P. Gerba, and I.L. Pepper. 2009. Survival of coronaviruses in water and wastewater. Food Environmental Virology 1: 10–14.

[7] Heger, S., ONSITE Installer. March 17, 2020. Are septic system professionals at a greater risk for COVID-19? https://www.onsiteinstaller.com/…/are-septic-system…

[8] Gundy, P.M., C.P. Gerba, and I.L. Pepper. 2009. Survival of coronaviruses in water and wastewater. Food Environmental Virology 1: 10–14; John, D.E., and J.B. Rose. 2005. Review of factors affecting microbial survival in groundwater. Environmental Science and Technology 39, no. 19: 7345−7356.

[9] Yates M.V. 1985. Septic tank density and ground-water contamination. Ground Water 23, no. 5: 586-591; Borchardt, M.A., P.-H. Chyou, E.O. DeVries, and E.A. Belongia. 2003. Septic system density and infectious diarrhea in a defined population of children. Environmental Health Perspectives 111: 742-748.

[10] Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. 2019. Subsurface Sewage Treatment Systems Well Setbacks. https://www.pca.state.mn.us/…/files/wq-wwists4-36.pdf

[11] Colorado Department of Natural Resources, Division of Water Resources. 2005. Rules and Regulations for Water Well Construction, Pump Installation, Cistern Installation, and Monitoring and Observation Hole/Well Construction. https://www.sos.state.co.us/CCR/GenerateRulePdf.do…

[12] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Will My Septic System Treat COVID-19? https://www.epa.gov/…/will-my-septic-system-treat-covid-19

[13] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Overview of Water-Related Diseases and Contaminants in Private Wells. https://www.cdc.gov/…/drinking/private/wells/diseases.html

[14] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Guide to Drinking Water Treatment Technologies for Household Use. https://www.cdc.gov/…/household_water_treatment.html…

[15] New York Department of Health. 2020. Information on Novel Coronavirus; Boil Water Response – Information for the Public Health Professional. https://www.health.ny.gov/…/response_information_public…

[16] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009. Well Testing. https://www.cdc.gov/…/drinking/private/wells/testing.html; and 2015. Well Treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/…/drin…/private/wells/treatment.html; National Ground Water Association. 2016. Water Testing and Treatment: What You Need to Know. https://www.ngwa.org/…/water-testing-and-treatment.pdf…; Schnieders, M.J. Well disinfection. In Water Well Journal. April 18, 2018. https://waterwelljournal.com/well-disinfection/

[17] National Ground Water Association. Annual Checkup [for wells]. https://wellowner.org/annual-checkup/

William M. Alley, Ph.D., is director of science and technology for the National Ground Water Association. Previously, he served as chief, Office of Groundwater for the U.S. Geological Survey for almost two decades. Alley has published more than 100 scientific publications, including the book High and Dry: Meeting the Challenges of the World’s Growing Dependence on Groundwater, co-authored with his wife, Rosemarie. Alley can be reached at [email protected].

Chuck Job is the manager of regulatory affairs for the National Ground Water Association. Prior to that, he worked at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for more than 29 years, having served since 2000 as its Infrastructure Branch chief. He is a former columnist for NGWA’s Groundwater Monitoring & Remediation. Job can be reached at [email protected].

WHO stands for World Health Organisation and most of their work is actually involved in tropical developing countries. So it is doubtful that their guidelines are solely focused on the temperate zone.

It’s possible that waterborne pathogens are at risk of being spread through ground water. But is SARS-COV-2 a waterborne pathogen. Although some strains of the virus have been detected in water, especially sewers, does it actually have a waterborne capability. As of current knowledge it has low airborne capabilities and the main medium of contract is via close contact with the infected.

Some frequently asked question on WHO. It also mentions about the waterborne capabilities.

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters

Here I prefer to comment on some the statements which mislead the public on COVID-19 pandemic

Statement: “In the process of decomposition of a human body, 0.4-0.6 liters of leachate is produced per 1 kg of body weight;”

“ The ex-filtration from sewers and cemeteries are the most likely source of human viruses to this groundwater system.”

Now we analyses above two statements: On average 28 liters of leachate is produced from one of COVID 19 virus infected buried 70 Kg body in its life time in the grave; 0.4-0.6 liters of leachate/kg will reach the ground water aquifer after several months or years. When leachate reaches aquifer, the virus particles will not survive for such long time, not be available even in trace amount or become non-infectious because of the weakly bonded spike protein(S) of COVID 19 virus could be decomposed due to soil temperature. Protein S mediates/recognizes the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor binding and membrane fusion between the virus and human cells.

But if one COVID 19 patient is admitted in a hospital for treatment or quarantine, he or she during bathing and washing, makes more than 28 liters of waste water daily basis and this waste water is mostly discharged into ground.

Now Sri Lank have about 50,000 infected people, imagine how much live virus infected water is discharged into Sri Lankan ground water and reaching aquifers [e.g. 50,000 x 28 =1,400,000 liter/day] so why this paper focus on least important COVID 19 infected dead body’s burial than the most important hospital or quarantine center’s septic, and sanitary waste water disposal? This paper really is misleading the public, students, and politicians of Sri Lanka. Unfortunately based on this paper, Sri Lankan law makers are also taking shameful decisions.

Another statement: “Several scientific publications report virus occurrence rates of about 30 percent of groundwater”, this is another much exaggerated statement. In all drinking water treatment facilities in all over the world including Sri Lanka, daily basis the treated water is quality tested for Total Dissolved Solids, Ions, and Microbes mostly for Bacteria only; not for the Viruses. The virus is not in the routine test parameters for each batch of water. This statement “Several scientific publications report virus occurrence rates of about 30 percent of groundwater’ escalate corona virus panic among general public. If this virus occurrence rate more serious, authorities might have taken the virus test parameter as routine mandatory test long time before.

Statement: WHO recommendation guidelines suit temperate countries mainly, not tropical high-temperature high rainfall countries. This is a very wrong statement. The corona viruses are not new to human and animal kingdom. In past many dangerous human corona viruses including HCoV-229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, MERS-Cov, SARS-Cov-1 etc caused diseases or pandemic. As per WHO recommendation, dead bodies were buried in all countries including temperate countries; these burials never created another pandemic situation due to ground water pollution in anywhere in the world.

So In this paper, the science supporting cremation of the COVID-19 infected dead bodies is not valid at all. This paper is also just a review of preliminary assumption only without any primary data for not to bury the dead bodies of COVID -19. Sri Lankan Scientific communities should double think before releasing or publishing such ambiguous notions.